April 2021

Wendy Schneider

A distraught son mourns his elderly mother after she dies alone in a long-term care home in Montreal. A woman sits shiva for her husband alone, denied the company of family and friends. A previously active senior, cut off from the activity that once brought meaning to his life, battles loneliness and depression. A mother, overwhelmed by juggling working from home with home schooling her children, asks herself, “What’s the point?” A developmentally delayed group home resident whose daily routines have been disrupted by the pandemic suffers from severe psychological distress.

As the coronavirus pandemic enters its second year, with new variants threatening renewed lockdowns, and no sign of most of us getting vaccinated any time soon, it’s no wonder many members of our community are struggling with intensified stress and anxiety. They’re not alone. The Canadian Mental Health Association recently published data that shows “alarming levels of despair, suicidal thoughts and hopelessness in the Canadian population.”

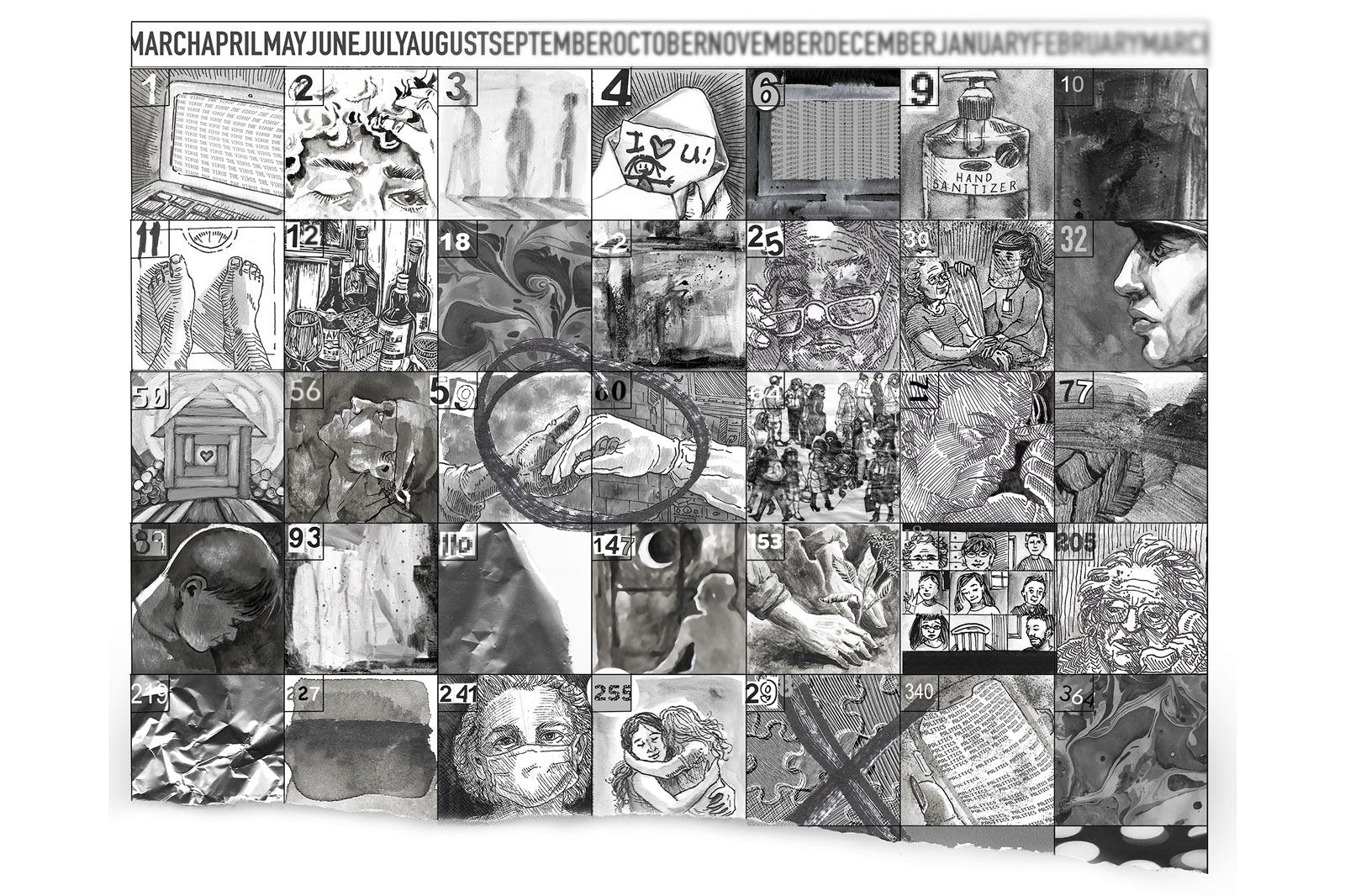

To understand the toll the pandemic has taken on Jewish Hamiltonians’ mental health, the Hamilton Jewish News reached out to professionals and community members over the last several weeks. While nearly everyone we interviewed spoke to the fear, uncertainty and anxiety arising out of months of social isolation, we also heard, in the words of the young mother who designed this issue’s front page artwork about “extraordinary gratitude, creativity and charity.”

What it’s like on the front lines

You can probably name at least one of your acquaintances who is struggling with his or her mental health. It may be someone elderly, someone who’s struggled with trauma from their past, an overwhelmed parent or a young person. The Hamilton Jewish News heard from a community member who wrote that, while she’s been through much worse in her life, she often finds herself “sinking into despair.” She often feels afraid, for herself, her daughter and for the “future of us all.” Though she’s enjoyed some “really good productive days” during the pandemic, on other days, she feels like she’s “holding on to the edge of the cliff.”

Gabriele McSween, a social worker with Hamilton Jewish Family Services (HJFS), has heard many stories like this one. Since starting with the agency last July, McSween has seen a huge increase in people seeking her services. By mid-February, she was counselling more than 100 clients every month, some of whom are long-time HJFS clients, but also many who reached out after attending one of her online mental health workshops. The most well-attended of these was a six-week bereavement course, which McSween plans to offer again due to popular demand. “That group was very connected with one another and they actually built a support group for each other afterwards, which was wonderful,” she said.

HJFS counselling services are provided free of charge and McSween’s clients, who range in age from people in their 20s to 90-year-old Holocaust survivors, are suffering from ongoing anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress disorder. McSween encourages people to set up daily routines like starting a gratitude journal, reaching out to family, friends or neighbours, limiting the time they watch the news and taking advantage of community resources like the HJFS kibitz corner, a phone-in program for seniors. Some of McSween’s clients are seniors who are terribly burned out from caring for a spouse who suffers from dementia. To them, McSween provides gentle advice about how to deal with someone with Alzheimer’s, while advocating on their behalf with a long-term care home.

McSween says she gets a lot of satisfaction from her work, especially when she sees clients feeling better.

The pandemic’s impact on the developmentally delayed

When the province first went into lockdown last March, residents at Beth Tikvah, the Jewish community’s group home for adults with developmental disabilities experienced “a tremendous amount of anxiety” due to an abrupt change in their routines, according to Beth Tikvah executive director Chris Barone. Not being able to walk from their Westdale home to their day programs, neighbourhood coffee shop or library, and denied the opportunity to meet with friends and family, had a profoundly negative affect on residents, said Barone. With the easing of restrictions last summer, Beth Tikvah folks were “just overjoyed that they could get back to some resemblance of routine,” but when COVID-19 numbers spiked again in the fall and winter, they experienced “frustration and exhaustion” from having their routines disrupted yet again.

The disruption of Jewish communal rituals

One of the most significant ways in which the pandemic has affected Jewish life is in how it’s disrupted communal rituals.

“There are a lot of rhythms of Jewish life that just aren’t there anymore and that’s very unsettling for people,” said the Adas Israel’s Rabbi Daniel Green. Nowhere is this more deeply felt than mourning rituals. “It isn’t so much what a person says when they’re coming to do a shiva visit. They’re next to you,” said Green. “The image that’s often used is you find yourself in a pit and you just want someone to come down into that pit with you. I don’t think Zoom enables people to come into a pit. From a soulfulness point of view, it doesn’t really fill that void.”

Rabbi Hillel Lavery-Yisraeli from Beth Jacob Synagogue said he’s had difficult conversations with the children of an ailing Shalom Village resident who have told him no one from the family, all of whom reside outside the country, will be able to attend her funeral should she die before COVID-19 restrictions are lifted. “I tell them that we as a community will take care of her, make sure she has a proper burial,” he said. “It’s absolutely heartbreaking, but what can we do? That’s where we are.”

People are, however, still finding spiritual sustenance when they need it. Attendance at Temple Anshe Sholom’s online services and adult education classes has tripled over the last year, according to Rabbi Jordan Cohen. His conversion classes have gone from an average of four or five applicants per year to 18 people in the current year. “On the one hand, I think the isolation’s really making an impact on people’s mental and emotional health, but at the same time, I’m seeing people actively reaching out trying to combat that by engaging in communal activities, in learning and in worship,” he said.

Hana Werner, a Toronto-based teacher of the Bible and Jewish history, would probably agree with that assessment. Seventy students regularly attend her Sunday morning Zoom Bible classes, up from the 40 to 50 regulars at her pre-COVID in-person classes at Toronto’s Adath Israel Congregation. Werner transitioned to online teaching last June with the technological assistance of former Hamiltonian Alan Cohen, who has uploaded all of her lectures to his YouTube channel.

Werner is a strong believer that a healthy mind is connected to having a sense of purpose. Many of her contemporaries have lost that.

“People, especially elderly people, you know what they do? They have a plan for one thing per day,” she said, such as an outing with a friend, an exercise class or a volunteer commitment. Now that that’s been taken from them, “there’s despair, tremendous fear and a tremendous loss of freedom.”

Werner though, appears to be thriving. Part of it is the mental stimulation from the hours she spends meticulously planning her 75-minute lectures. But there is another reason.

“Never, in the winter time, did I venture out the way I’ve been venturing out. I don’t like winter,” she said, “But by the time I get dressed up with a mask and a scarf, coat, boots and gloves and all of that, I’m ready to go.” And go she does, at least three times a week, for 90-minute outings around her North York neighbourhood.

Vulnerable seniors see cognitive decline

For many seniors, however, health conditions like poor eyesight, arthritis or Parkinson’s disease, are keeping them confined to their homes, leading to, what Rabbi Green observed, is an alarming increase in cognitive decline among some of his congregants.

“The people who were having cognitive difficulties, they now have limited all their interactions with the outside world and are curling up. The decline is often astonishing,” he said.

But the rabbi is just as concerned for parents of young children, who he senses are having a difficult time, particularly when schools turn to online.

“Parents need space. They need space even if they’re not working, but particularly if they’re working. It’s really untenable,” he said.

Janet Weisz, who practices pediatric medicine in Burlington, is not surprised that parents are stressed. In an op-ed she penned for the Hamilton Spectator in February, Weisz referenced the significant increase in anxiety, depression, anger and eating disorders that she’s seen in children and teens since the onset of the pandemic. She told the HJN that much of this is related to the cyberbullying, which has worsened with younger people spending so much time in front of their screens. Weisz said she fears these issues will remain a problem after the pandemic due to a lack of funding for children’s mental health.

It’s not all bad news

The pandemic has had a negative impact on countless individuals, businesses and society at large, but it has also presented us with a unique opportunity to reflect on our lives and evaluate how we spend our time. Former Hamiltonian Sari Richter and her husband are raising a toddler in a Toronto neighbourhood with many other young families. Richter told the HJN that she enjoyed the way life slowed down “to a glacial pace” in the early months of the pandemic.

“There were no programs and activities to run off to. Parents weren’t spending hours commuting,” she said. “My husband was working long hours from home, but it still afforded him more time with us.” From May to November, Richter enjoyed a newfound simplicity of daily walks with her daughter to the park.

“We’d watch dogs, kick a ball, read under a tree, chat with friends and playground acquaintances from a distance in the big field,” she said. “Many days seemed to be exactly the same, and I missed our family and friends terribly, but I loved the grassy, sun-drenched smell of her curls after a day together outside.”

Before the pandemic, Benson Honig, a McMaster University professor in the DeGroote School of Business, was accustomed to boarding a plane every six weeks for a faraway destination to give a talk at an international conference. Now, he spends his time writing grants for programs to support budding entrepreneurs in developing countries. Honig said the COVID-19 pandemic has given him the time “to sit and think about what’s important.”

“I have a very strong hunch that this COVID year may be one of the most important and successful years in my life in terms of creating new opportunities, rethinking what I’m going to do… given the tools that I have and the opportunities that are available to me.”

When Cindy Mark’s income from her dental consulting business took a drastic hit during the first lockdown, her sense of self took a similar nosedive. But Mark eventually used her freed-up time to pursue an idea that had been percolating inside her head for quite a while. Today, she’s transitioned from coaching dentists to facilitating mutual support and accountability groups for solo entrepreneurs. Mark also volunteers with Out of the Cold and Hamilton Jewish Family Services, where she heads up its food bank committee. Mark says that losing her income was a huge hit on her self-worth, but she is very grateful that COVID-19 brought her back to volunteering.

Richter feels grateful too, although there were moments, especially at the beginning of the pandemic when she had to remind herself that she was “incredibly lucky.”

“At the very least, I can use ‘It’s fine, you don’t need to call. I only raised you in a pandemic,’” as my go-to Jewish guilt line on my daughter for the rest of my life.”

Art by Sari Richter

RELATED: Hope and resilience at Shalom Village